Photo: Mario Jiménez Leyva — Noticias Oaxaca

Afro-Mexicans on the Oaxaca Coast

Photo: Ernesto J. Torres, Casa 12

When you see me it’s obvious from the color of my skin (light brown) and my curly black hair that I am of African descent, but you will also note indigenous and European features – in sum I am what is called Afro-Mestizo. Thus I am similar to many people on the Oaxaca coast, especially in Tututepec, Jamiltepec and Pinotepa Nacional and other neighboring municipalities. But when I did my university studies in Cuernavaca four years ago, I discovered that many Mexicans were ignorant about the existence of people like myself. They thought I was from Veracruz or Cuba; I was even asked if I was from Jamaica. And of course they knew nothing about the history or traditions of my people.

Photo: Ernesto J. Torres, Casa 12

Our history begins in the 16th century when the Spanish brought African slaves to the coasts of Guerrero and Oaxaca to work on the cattle ranches and cotton plantations. From the beginning, some slaves, most of whom were men, managed to escape and to live with the indigenous communities. Meanwhile the African women suffered from rape or cohabited with Spanish men. There were also slaves who fled and formed their own communities in places on the coast that even now are difficult to access; rhere they developed their own customs and traditions.

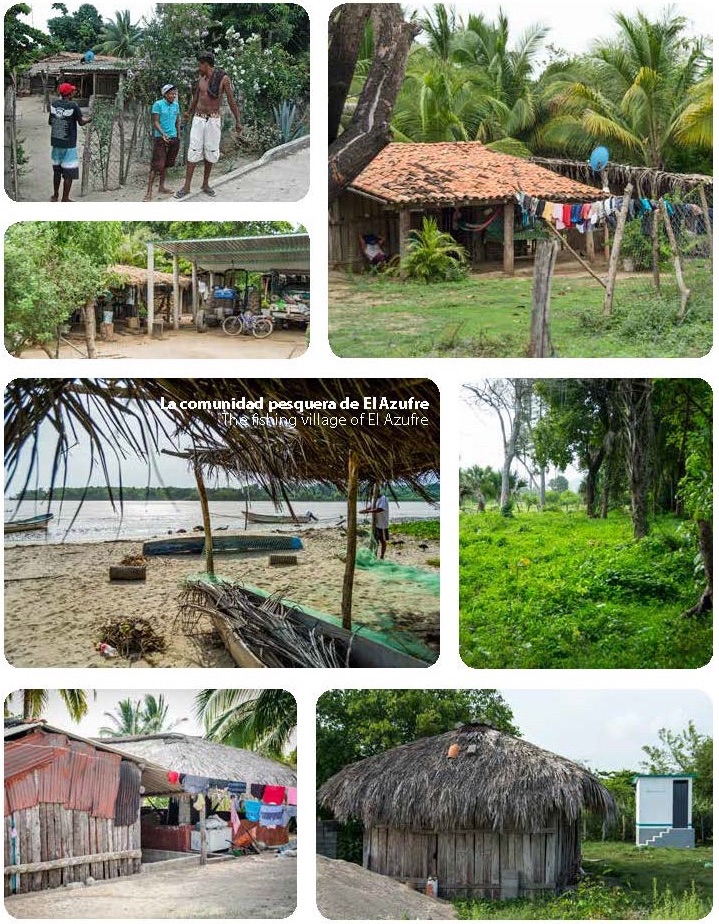

Today, the African influence is felt in the food, traditional medicine, and the music and dance that set the Costa Chica apart from other regions of the country. There are, for example, compounds of round houses in Chacahua that stylistically can be traced back to Ghana and the Ivory Coast. The cajón and the bote (a friction drum that imitates a lion’s roar), the quijada (made from the jaw bone of a burro) are instruments of African origin, as is the Dance of the Devils (Danza de los Diablos).

At my uncle’s wedding in a small, Afro-mestizo village in Guerrero the women, wearing long, colorful, ruffled skirts, danced in a circle with beer bottles perched on their heads from which they would take a sip from time to time. The men danced in another group but with the beer bottles in their hands and a machete or pistol hanging from their waists.

Later I asked my grandmother how it was that the women could balance the beer on their heads, and she explained that their skulls had been flattened from years of carrying tubs of laundry to the river for washing. Some traditions might best not be passed on.

According to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), there are around 1.4 million Mexicans of Afro-mestizo descent, but the federal government does not recognize us as an ethnic group, mainly because we do not speak an indigenous language. Thus Afro-mestizos do not receive the aid given to indigenous communities.

This is the situation that the Itinerant Conference for Women of African Descent (Cátedra Itinerante para Mujeres Afrodescendientes — CIMA), which met in Puerto Escondido last May, wants to rectify. The six women of the council – Rosa María Castro (Charco Redondo), Juliana Acevedo (Morelos, Huazolotitlán), Yolanda Camacho (Santa Rosa Tututepec), Sandra Luz Villalobos (Ciudad Ixtenec) and Beatriz Amaro (Lo de Soto) – are focusing on the condition of Afro-mestizo women because of the scarce resources available to them. Most can not read or write or have not completed elementary school, and they are the victims of racial discrimination, xenophobia and violence.

CIMA began with the help of the National Commission on Human Rights (CNDH) and the Benito Juárez Autonomous University of Oaxaca (UABJO). It is a non-profit organization which hopes to attract more participants to its conferences. For information or to make a donation, call 958 115 3632 or e-mail casalros@hotmail.com.

Photo: Gretell de Gala

Locally, Eva Victoria Gasga Noyala works with the Afro-Mexican communities in Tututepec (the municipality west of San Pedro Mixtepec) through Ecosta Yutucui. She was our guide to Charco Redondo and El Azufre. She is also on the advisory council of the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI) and has been active for the last five years in the struggle to achieve constitutional recognition for the Afro-Mexican communities so that their voices may be heard and their concerns addressed. You can contact Eva at 954-113-6076 or gevavictoria@yahoo.com.mx.

Afro-Mexican Communities of Tututepec