La Punta: the Founders

Those who know won’t say, and those who say don’t always remember. In broad strokes, this is a rough draft of the history of Brisas de Zicatela (the Punta).

The conflict between the municipios of Santa María Colotepec and San Pedro Mixtepec over Puerto Escondido goes back at least to the 1920s when the coffee from Nopala and San Gabriel was shipped from the Playa Principal. (There was no dock, and the coffee was borne on flat-bottomed canoes to the ships waiting offshore.) According to one 19th century geographic survey carried out by the state of Oaxaca, Puerto is part of San Pedro Mixtepec; in another it is shown as belonging to Santa María Colotepec.

Colotepec ceded its claim to Puerto, including all of Zicatela, to San Pedro Mixtepec at a meeting with Governor Victor Bravo Ahuja in 1969 during which they were promised electricity, potable water, roads, and a health center. Another story is that money changed hands. These projects were to be paid for by the State through the Fundo Legal de Puerto Escondido within five years. The State did not comply with the terms of the agreement.

In 1970, President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz signed the expropriation decree which privatized the coast of Puerto Escondido from the Cerro de la Vieja, near Chila, to the Punta de Zicatela. The land was given to the Fundo Legal de Puerto Escondido to develop tourism, but Fonatur, the federal agency for tourism, administered and financed the project with funds from the Bank of Mexico.

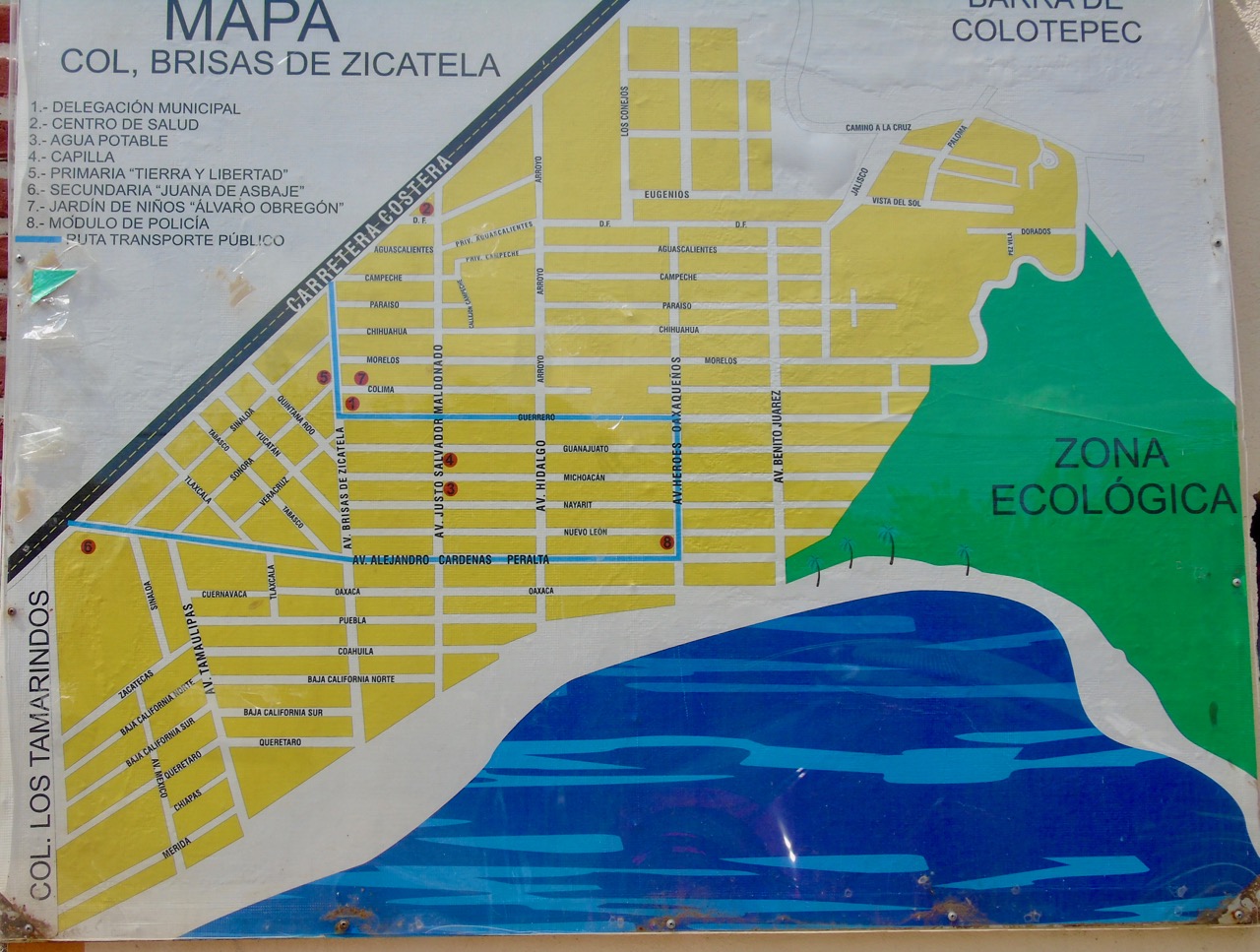

Fast forward to 1982. There are no resorts outside of Bacocho, but the Fundo Legal de Puerto Escondido, now called the Fideicomiso de Puerto Escondido (FIPE) is still a player. Colotepec still lacks electricity, potable water, roads etc. Alejandro Cárdenas Peralta, a native of Pochutla, is the federal deputy for District 30 which includes Colotepec. (San Pedro Mixtepec is in District 22.) Justo Salvador Maldonado is the newly-elected president of the Bienes Comunales of Colotepec. The two men lead an “invasion” of Brisas de Zicatela, reclaiming it for Colotepec. (Alejandro Cárdenas is murdered in February 1985, and Justo Salvador five years later. Neither death seems related to the invasion/recovery of the Punta.)

The land is virgin forest: huizache trees with long thorns and mesquites. There are cougars, coyotes, rabbits, a few deer and lots of scorpions. Justo Salvador issues a proclamation offering actas de posesión on lots of 25 x 25 or 15 x 20 meters (depending on the location) to anyone from anywhere, not just from Colotepec, who is willing to help clear the land. There are advertisements in newspapers and on the radio. Some people come from Miahuatlán (there is already a history of migration from that region to Puerto) which is the birthplace of Justo Salvador.

Amancia Márquez Reyes, proprietor of the restaurant “Doña Amancia” on calle Tamaulipas, was a 40-year-old widow with 4 children living in rented rooms in Puerto’s Colonia Benito Juárez in 1982. A native of San Pedro Atoyac, a small municipio in the mountains near Pinotepa Don Luis, she came to Puerto after having lived many years in Jamiltepec. There were many widows like her who responded to Justo Salvador’s call. Their job was to clear the branches the men cut with their machetes. When she was given her lot, she built a palapa for her family.

If you have spent time on the restaurant strip above the beach in the Punta, you probably know doña Adelina (Adelina Adolfina Santiago Noyola) as a woman who has worked at various fruit stands and hostels, including Frutas y Verduras. The 74-year-old native of Acapulco was living with her sister in Puerto on Camino a Puerto Angelito in 1982. Like the other founders, she worked clearing the land and was given a 25 x 25- meter lot three blocks from the beach on the corner of Heroes Oaxaqueños. First, she built a simple palapa but continued living in town, but in 1986 she moved with her children to the house she still lives in.

What the feisty doña Adelina most remembers of the 1980s in the Punta is the struggle to be connected to the electric grid. Even after the power lines were installed, they weren’t in operation. The Oaxaca authorities in Puerto said that there were technical problems and kept putting the residents off. Finally, in December, 1990, she recalls, she marched with a group from Colotepec, armed with pointed sticks, to the state offices in Bacocho. The secretary said that the official was not there. But his car was parked out front, and they knew he never went anywhere without it. So, they burst into the room where the man in charge was meeting with two other officials.

“We told them that if we didn’t have power by Christmas we would tie the three of them to the electric poles.” The lights came on a few weeks later. On the other hand, Adelina has chosen not to be connected to the water system, preferring to get water from her well. Adelina shares her two-room house with her son, the surf instructor, Juan Manuel Cruz Santiago.

In 1984, Filogonio (Filo) García Altamirano was a 36-year-old shark fisherman. The native of Ventanilla, Colotepec had moved to Puerto as a young man. He remembers participating in the meetings of the Bienes Comunales when it was decided to recover the land that had been ceded to San Pedro. Once the land was cleared and simple houses built, the first job (tequio) of the community was the digging of three communal wells. Filo points to the municipal police post on Héroes Oaxaqueños as the site of a well where the residents drew water for their homes in the early morning and late afternoon.

By 1989, there were 16 families living in Brisas de Zicatela, according to José Ramírez, who is currently vice-president (suplente) of Santa María Colotepec. The lots that were not allocated to the people who cleared the zone were sold by the Bienes Comunales, with land closer to the beach costing twice that of land closer to the highway.

He also recalls the problems with getting electricity. In that year, governor Heladio Ramírez López recognized Colotepec’s claim to the land previously ceded to San Pedro. This was meant to facilitate the purchase of land on Zicatela by a Japanese company which wanted to build a resort there. The hitch was that the land was occupied.

Despite resistance by the State, three electric posts with transformers were installed in 1989, one on Heroes Oaxaqueños, one on Av. Guerrero, and another on Av. Brisas de Zicatela. The municipality of Colotepec paid 80% of the cost and the residents 20%. Once there was power, in 1990, more people came to live in the Punta.

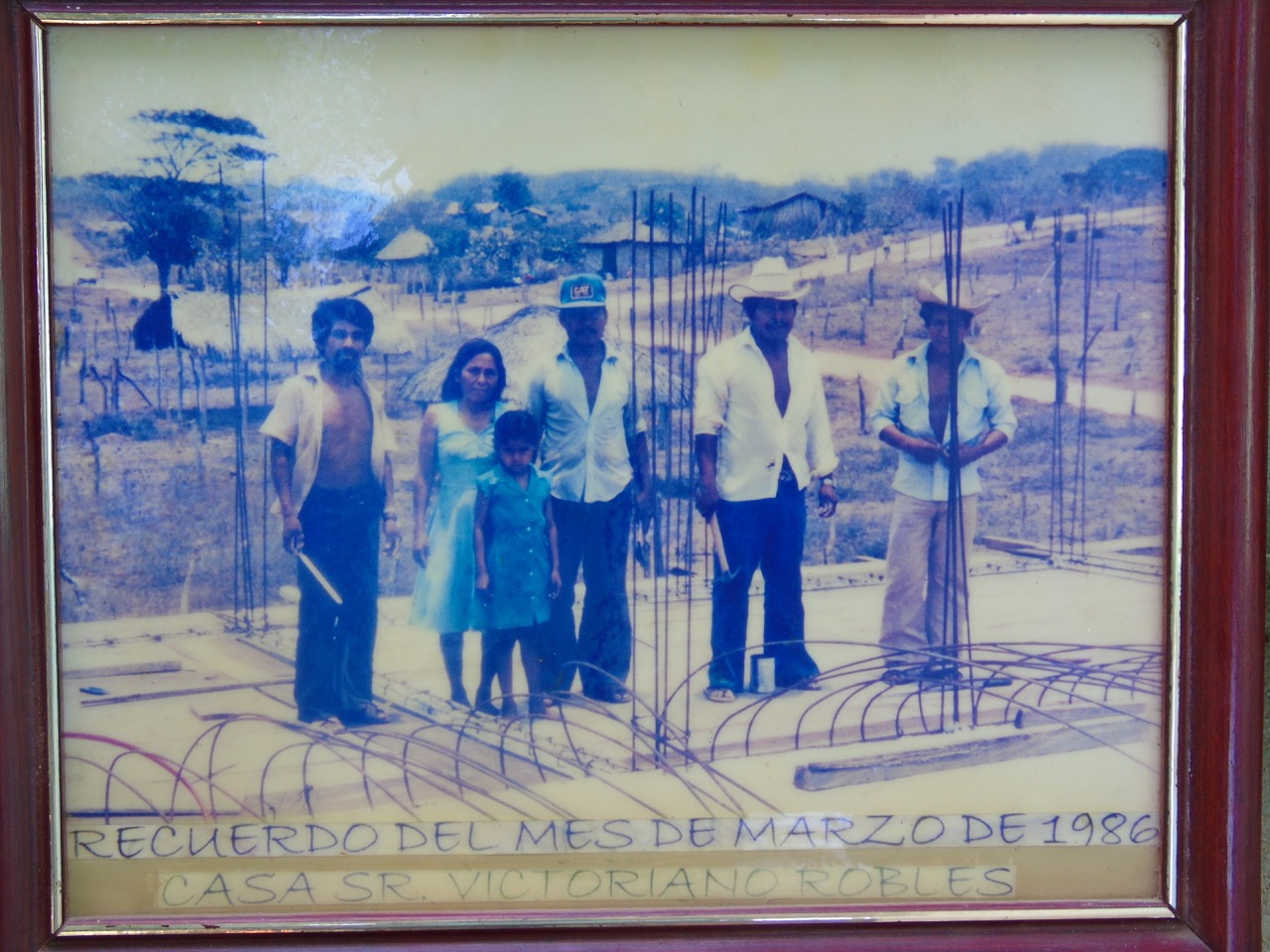

The lack of electricity was never a problem for Victoriano Robles and his wife Zenaida Jiménez. They were farmers in Santa María Colotepec who had always lived with kerosene lamps. The attraction to living in the Punta for them was the primitive school house — just a palapa with wooden benches — where they could send their 7-year-old daughter in 1984. Victoriano was then 50, and besides growing corn and sesame, he had cultivated peanuts in Tomatal — with a plow drawn by two, rented, oxen. This gave him the funds to build his house that now has 3 stories. In the Punta, Victoriano and Zenaida found work maintaining the lots of absentee owners.

Most of the people who were given lots, or bought them, did not live on them. Typical was the case of José Silva’s mother who supported her family in Puerto by making tamales. She and her sons cleared the land and were given a lot which they fenced and maintained. She sold it in 1996 to cover the costs of a family emergency. Others sold their lots to buy livestock or pick-up trucks. There is no doubt but that many poor people profited by the distribution of the land.

The recovery/ invasion of Zicatela led to the area being legally designated as a “zone of conflict” between the two municipalities. Up until a few years ago, the land was still mostly unoccupied, record keeping was bad, and some of the local authorities were venal. New actas de posesión got issued, and it was not unheard of for there to be two or more actas for the same lot. Today, however, the situation is much improved.

Oaxaca’s plan for international resorts in the Punta never came to fruition, but the last 15 years have seen a boom in vacation houses and apartments. Electricity is still a problem. There aren’t enough transformers, and illegal hook-ups are common. Since the land is communal – administered by the Bienes Comunales of Colotepec - only Mexican citizens or Mexican corporations can be issued an acta de posesión. Although some lots have titles (escrituras) from the land office in Pochutla, these titles are not valid in property disputes which are settled by the Agrarian Court in Oaxaca.