Photo: Ernesto J. Torres, Casa 12

Cockfights in Chila

From our archives, Spring-Summer 2016

When chickens were first domesticated 8,000 years ago, it wasn’t as a new source of protein. According to evolutionary geneticist Greger Larson, for thousands of years they were bred just to provide roosters for cockfights and religious rituals. An archeological dig in Israel has concluded that they were first raised for food only 2,200 years ago. There are many references to roosters in the bible, but only two to hens (protecting their chicks), both in the New Testament.

Amazingly, the ancient tradition of cockfights continues to the present day with gamecocks being bred for their stamina in the pit. With that in mind, we visited Chila’s largest gamecock breeder, Omar Aragón Escamilla. Omar, like the roosters he breeds, has cockfighting in his blood. He is the son of don René Aragón Bohórquez, who with his brother Alfredo, created Chila’s first palenque (cockpit) in 1973 under the mandimbo tree in front of the primary school, and he is a passionate devotee of the sport.

“You don’t have to teach a cock to fight,” he explained to us, “because they are naturally very aggressive. But you can help them develop their muscles.” He showed us a ramp with a 45-degree angle he uses for training.

It takes around two years before a gamecock is big enough to fight; breeding is a serious business since so much depends on care and fodder, and lineage, of course. Professional breeders from all over Mexico and even Las Vegas enter their birds in the annual Aragón palenque which coincides with Chila’s February San Isidro fair.

Omar is very proud of the professionalism of his palenque. Cocks are only allowed to fight in their weight category. Before each event, the cocks are weighed-in so that a 2.2 kilogram animal cannot fight one weighting 2.3, for example. He also believes that one must have respect for the birds and the tradition they represent. People deserve a spectacle, he says, and there is always a band playing between the fights at his palenque. There are also four screens over the cockpit showing the fights in real time.

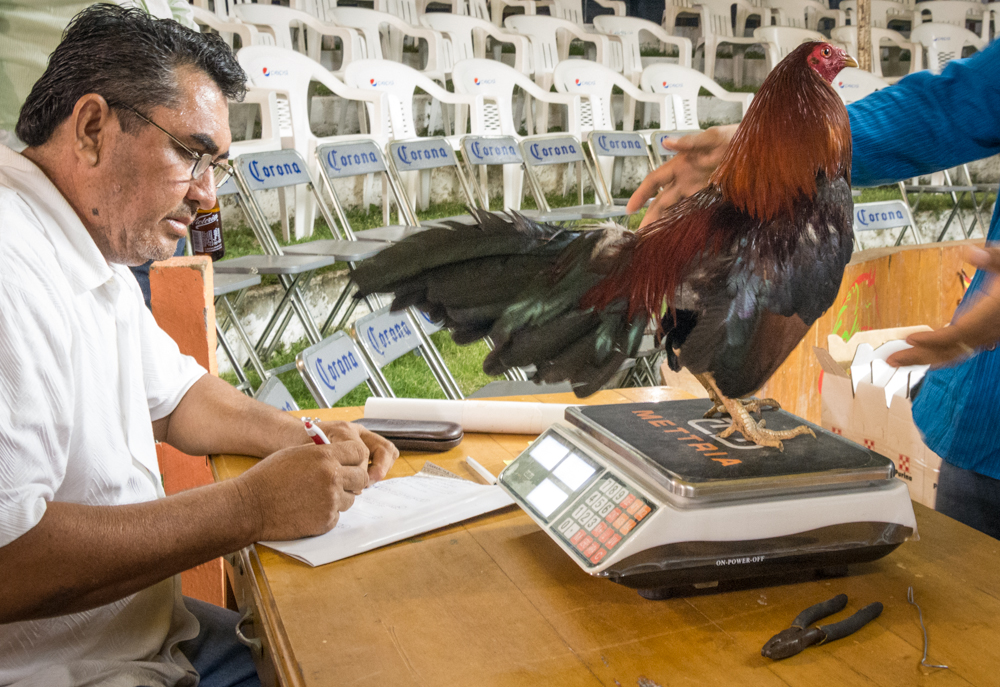

First comes the weigh-in with the judge. It’s not always easy to keep the cock on the scale long enough for it to register, even with an electronic scale. Each bird is then given a numbered tag affixed to a leg. After all the cocks are registered, there is a drawing to determine which bird fights with which. The breeders had to enter five gamecocks in the February 12 Super Derby, but if they lost both fights in the initial two rounds, they were automatically disqualified from the final rounds.

Before the combat, a one-inch knife is attached to the bird’s left foot. Then the two trainers hold up the birds on opposite sides of the pit while a prep (teaser) cock is brought over to get their juices going and to show the spectators their stuff. This is when most of the bets are made. Finally, a cloth is passed over the blade and then over the rooster’s beak. This is to certify that the knife has not been poisoned.

You don’t have to bet at a palenque, but it sure adds to the fun. One side of the pit is red, the other green. You bet on red or green. Really simple. There is a professional crew of bet takers offering red and green tickets. The problem is that each bet has to be matched; there are no odds. You might want to bet on red, but only green is available – because you waited too long or because the heavy betters got preference. The night we went, the minimum bet was 500 pesos. The house takes 20% of the winnings, so a 1,000-peso wager means either you lose $1,000 or you win $800. On the other hand, there is no rule against your making side bets with your neighbors.

The honor of the cockfight demands that no money is shown during the betting. It isn’t until the fight is over that the losers hand over the amount they had wagered.

And now the action begins. The two gamecocks go after each other with their feathers all ruffled leaping into the air. After that, it tends to be more of a slugfest on the ground. Usually the bird whose beak hits the dirt first is the one who will lose. But the rule is that the fight must go on for 12 minutes or until the death. Occasionally, if neither bird (or both) has its beak in the dirt at the end, there is a draw. If there is no activity for 15 seconds, a 15-second break is called so that the trainers can blow the dust off their beaks and otherwise revive them. After the first five minutes the knives are changed.

After the fight, the survivor’s wounds are sewed up. A gamecock that has survived four or five fights is considered a champion and may enjoy his remaining years as a stud. Omar knew of a cock that won 17 fights before he retired, undefeated. He was called the General. It’s always best to bet on the veteran; the bird with the most scars is considered the most valiant.

The Aragón palenques typically begin the weigh-ins at 9 pm and the fights at 11. They go on all night into the next morning. We only stayed until 1 a.m. The spectators were mostly men and generally relaxed. I don’t know what the mood would be like at 6 when a lot of money would have changed hands.

Palenques like those of the Hermanos Aragón are regulated by the Ministry of the Interior (SEGOB), which considers them an important manifestation of Mexican traditions and culture, as well as being of economic value.