Zicatela: A Beach, a Wave and a “Whale”

You are the sea

I am the sand

I’ll go with you

Wherever you wish.

“Al Padre Santo de Roma”

by Camerón de la Isla

“The beach belongs to the ocean.”

Robin Cleaver, owner of the Hotel Santa Fe.

I was completely unclear on the concept. I thought the beach was a strip of land covered with sand that God in His wisdom had created for the purpose of placing deck chairs. When giant swells carried the sand away, it looked like erosion to my untrained eye: the devil undoing the Lord’s work. Now I see the beach as the exposed part of the ocean floor and its shifting size and contours as part of a much larger ecosystem which includes turtles, crabs and rays.

The large swells generated by winter storms in the South Pacific arrive on the Oaxaca coast during our summer. (These waves, which come from as far away as Chile and New Zealand, do not actually move molecules of water along their trajectory, just as radio waves do not move the air they pass through.) When extremely large waves converge with the highest tides and half the beach is washed away, a new seascape is made from the sand below the waterline.

Zicatela, the “Mexican Pipeline”, is the foremost beach in Mexico for surfing, and its competitions are part of the circuit for professional surfers. What makes the Zicatela wave so exceptional is a combination of factors that include the shape of the beach, the local winds and the contour of the ocean floor – the trenches and the everchanging channels.

Yet Zicatela’s fabled waves are ever endangered by whatever would inhibit the free flow of the sand or the off shore wind. Some long-time surfers here say the waves used to be better and they blame the rainy season run-off from Lázaro Cardénas, the community on the hillside above the highway, for creating a densely packed, dirt floor under the water.

This year the beach faced another threat: a cement construction inside of the area where the ocean and sand still are free. The proposed restaurant/bar formally known as “Number One”, but referred to locally as the Whale, because it was to have a façade in the shape of the Leviathan, was going to be the highest building on Zicatela – 5 meters of construction plus a palapa - and people familiar with the project said the intent was to turn it into a disco.

Apparently, the developer, Ivan Negrisoli of the Mexican corporation, Rawe Party SA de CV had all the necessary permits from Colotepec, as well as a permit from SEMARNAT the federal environmental agency, when the construction began in March of a cement foundation closer to the shore line than any of Zicatela’s palapas.

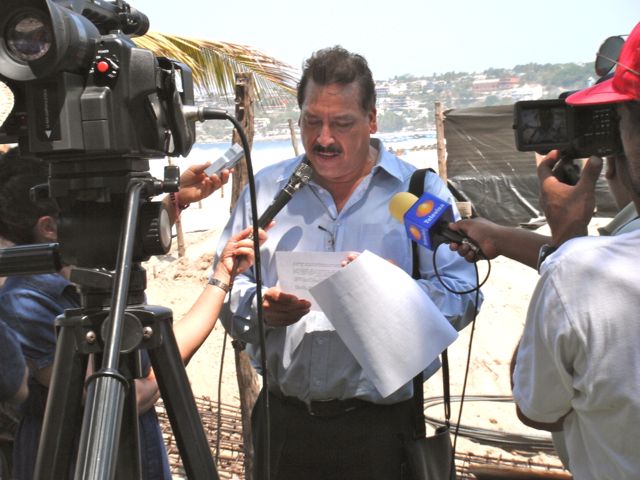

On April 19, the Hotel Owners Association of Puerto Escondido, led by its president Austreberto Garfías Arandía of the hotel Olas Altas, staged a protest at the site and issued a “citizen’s closure”. These were not your Occupy Wall Street types (although on a separate front, a Facebook page set up by surfers in San Diego had also put out an alert) but rather middle-aged business people who are the backbone of Puerto. Hotel occupancy is the economic indicator of Puerto tracked by the state government, not real estate prices or restaurant/bar revenues. The hotels are not only major employers, but they also pay the lion’s share of local taxes.

The hotel owners main concern was to maintain Zicatela’s natural beauty and to keep it from becoming a noisy honkytonk. It’s easy to imagine it being Semana Santa every weekend once the highway to Oaxaca is completed, if the beach were allowed to become party central. And that would spell the end to national and international tourism as we know it.

It wasn’t just a question of money. Unlike Huatulco or Playa del Carmen, Puerto’s hotels are independent operations, and, since most of the hotel owners live here, they have a real stake in preserving the environment. If the Whale was allowed to proceed, other similar-sized constructions would follow.

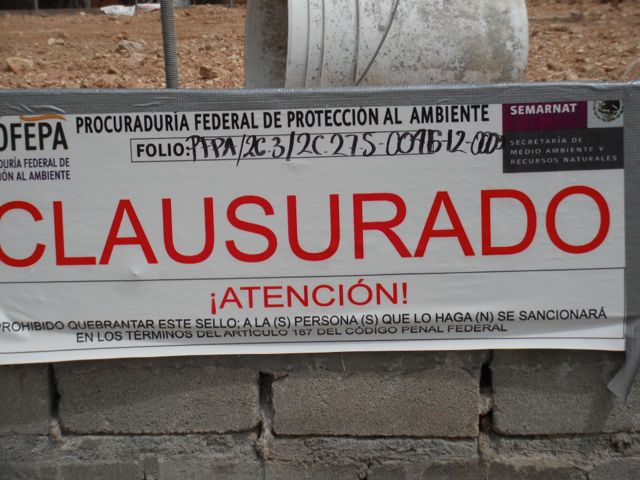

In an interview the week after the protest, Silviano Cruz, the commissioner of tourism for Santa María Colotepec, told ¡Viva Puerto! that the Whale would only be permitted to build a restaurant/bar palapa similar to Grekos. Nonetheless, construction on the foundation continued until June 29, when the site was closed by PROFEPA, the agency that enforces environmental protection laws in the federal zone.

The 19-page PROFEPA report noted a number of irregularities in the method of construction that led to the contamination of the sand, water, and air. The first infraction, however, was for the size of the project which exceeds the 240 square meters of the concession.